I recently made a trip up to Chicago to see my long-time brother-in-kilt, Matt Solomon. Both being gamers who are usually the GMs or who have limited access to gaming groups, we wanted to get into some good gaming during the trip. But there were only two of us and we both had been starved for the actual play experience for quite some time. So, which one of us would give up the chance to play to run a one-on-one session for our friend? Neither.

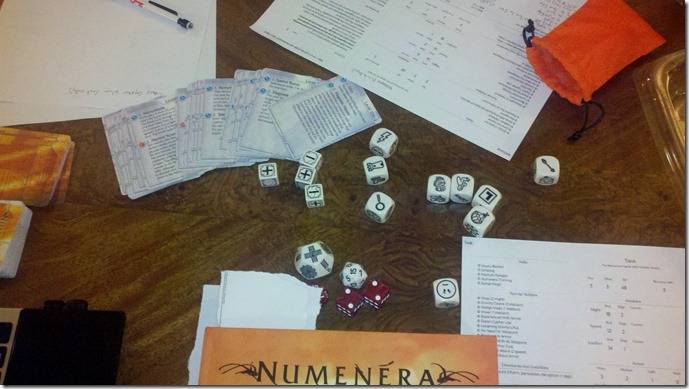

As we sat around enjoying our frosty beverages and determining what we wanted to do, we came up with the idea of running the game collaboratively and taking turns as Gamemaster. We had just finished playing some Sentinels of the Multiverse (a cooperative superhero card game played against a ‘Villain’ deck) and drawing inspiration from games like Fiasco, we pulled out my copy of Numenera and set about figuring out how to make this work. The end result was fairly smooth and provided a great game, so I want to share the experience so you can mine it for the gems that might fit into your games.

Background — The Lenticular Adventures of Williams And Tank

Let me start off with a bit of ‘let me tell you about my character’ background, just so that you understand where we were coming from when we put together this method of doing collaborative GMing. I’d been pitching Numenera to Matt for a while, talking up the ease of character creation and running and the general openness of the world. We started to talk about running a game, and initially I offered to run it as a one shot for him with a backup NPC, but after the Sentinels game we got it into our head that we could wrap it together and take turns. Redoing our characters, this is what we came up with:

Williams — Matt was inspired by the smooth talking, bold character of Williams in Enter the Dragon. Grabbing the general idea of Williams, mixing it in with a little bit of Cowboy Bebop, and adding in the Howls At The Moon option in Numenera, Matt made himself a smooth talker who was a bit full of himself, but full of options and comebacks for every situation. He also got a little hairy when things got hairy and his bare fisted style and bolt thrower crossbow device weren’t enough.

Tank — My original character concept was a big (as in guido from x-factor disproportioned body big), dumb, brute who barely spoke and followed Williams around, letting him be the player but providing some backup. With the possibility of being able to play, I redid my character as a big, smart, but quiet white-haired brute with pince-nez glasses whose curiosity got him into trouble and who could whip gravity around like it was mashed potatoes. Having a futuristic samurai vibe, Tank was a huge guy who quietly kept looking at, trying on things, and pushing buttons in the background until something interesting happened.

Having a kind of Cowboy Bebop, anime vibe to our night and already feeling quite cheeky, we knew that even if someone were willing to GM for us, they’d have their hands full and probably never want to play with us again. With our characters in hand and a feeling for what our game style was going to be like, we set about coming up with a structure to run the game at the same time as playing it.

The Collaborative Structure

There were a lot of things we did to make the Lenticular Adventures of Williams and Tank work smoothly. Some of these came about organically, some were discussed beforehand, and some were the result of situations going badly and us taking a break to have another drink and figure out how to make it work better. These are the primary structures we came up with.

- Taking Turns and Listening To The Arbiter

The first thing we did was agree to take turns as the one running the game and the one who the story/game focused on. Each ‘scene’ we would hand off the GM’s hat and narrate to the other person. While we would both act out our characters in the scene, the one who was GMing would also act out the NPCs, etc. and control the mechanical elements and difficulties. The person running the game had FULL control and the person playing would not question their authority. Neither of us were above the other, but had the same amount of power and investment as both a player and a Game Master. - Set The Goals/Structure Beforehand and Let Spoilers Be Danged! — We set a goal we would be working towards, right from the front knowing that this was what we were aiming for in our adventure. With us both being in charge of running the game, things like secrets and reveals were not really possible, so we made the conscious decision to let the spoilers be darned. If something, like a trap, was in a scene and was secret, it would be so only for that scene or be in control of that GM whenever it was encountered again. Making a guideline for our story, we knew we had a structure to fall back on. Ours was:

– We discovered a glove in a ruins for a buyer

– We needed a key for it

– The key was in a cave… somewhere

– We needed to find out where

– The cave was guarded

– The cave was trapped

– The cave was ancient and part of a cult - Tailored Goals — The goals of a scene would be focused on the person being a dedicated player at the time. Matt would run a scene where I was in a room filled with gold covered walls and a weight puzzle (due to my gravity abilities) and I would run a scene where he could sweet-talk a map and some cyphers from a travelling caravan. As we ran the scenes, we focused on things that the other player could and would want to do instead of things that fit a more general feel. If someone felt like doing something, they would tell the other one. “Hey, give me a puzzle. I think that would be cool.”

- Combats — Numenera was a key part in doing the shared GM structure, due to the fact that the GM never rolls. Running combats became easy, with the GM directing the creatures and enemies and not taking it easy on any character. We used dice rolls at times to figure out who would be attacked or let the logic of the situation rule the day. Did Tank make the big noise that alerted the Ithsyn? Ok, Tank is the one first jumped. Did Williams break out into his Big Bad Wolf form and roar, then he is the biggest threat and the snipers aim for him primarily.

- NPCs Owned By All — We agreed early on that playing out any NPCs would only really interact with the player, prevent the talking to yourself option. The NPCs would not be played by only one player, but by whoever happened to be the Game Master at the time. It could have some odd instances where an NPC felt different under each GM, but nothing that hindered the game or made it less fun. If Tank would fail at convincing an NPC to help out, he’d ask Williams to help. Matt would roll based on the same difficulties (or +1 or 2 higher due to failure) and then Matt would shortform the conversation so that it didn’t take up time in the scene.

- Random Determiners — A lot of the success of the game was in us taking some of the control out of our hands. We used Fudge dice to determine general reactions of NPCs, difficulties, and the likelihood of ideas. Rory’s Story Cubes were rolled often to give us inspiration for the next scenes.The Numenera cypher deck was used to create artifacts and cyphers during the game, with a random draw or rolls from the tables in the book supplementing some of the options. At one point, we were searching for someone who knew where the cave with our goal (a key to remove a glove that Tank had slipped on, just to see how it fit, and now couldn’t get off) was. I rolled some story cubes, picked out and interpreted a few of the symbols for inspiration, then Williams went up to talk with the caravan driver. Rolling some fudge dice to determine the general attitude, Williams made his rolls and had a hard time getting some of the information, but he eventually got it. We used some random dungeon path dice to determine the layout of the cave once we got there an each new room was another scene, unless it contained nothing and then it just lead to the next scene.

- Plot? — The back and forth nature meant that this would not be a game of high intrigue, but one of dealing with smaller challenges in pursuit of a larger goal. We outlined a few things we wanted to happen during the game, and then ticked them off a list. As the plot veered far off the general course and back into it, we had a lot of fun figuring out how to get to the next goal. When I was running the game, I would use my PC to help springboard back (having him stick his hand in the glove, giving us a reason to pursue our final goal of finding the other piece of the artifact), and when Matt was running he would use Williams to push things along (like getting us kicked out of the caravan because he mouthed off to the wrong person, leaving us stranded but with a reason to be on our own so we could be attacked by bio-organic snipers who were part of the cult).

- House Rules — We realized fairly early into the game that we would need at least a few house rules to make this work. Since Numenera has a system to lower the difficulty of rolls before they are made, we decided that this would be perfect to use to keep the action moving. We made the decision that you could spend Effort after a roll (instead of before) to make it succeed and that the task difficulties would always be in the open. This removed some of the up-front difficulty, but it made it so that success could be achieved at a price and the action could keep moving. Since Might also acts as hit points in Numenera (as do the other pools of attributes), we still took ‘damage’ but the damage enabled us to succeed at a task instead of just getting hurt. This made plenty of narrative failures that moved the story along, like letting the Ithsyn bite William’s whole hand so that Tank could get a chance to cleave it in two while just scraping the skin on William’s knuckles with his sword.

What Made It Work

By the end of the two nights worth of gaming we did, Williams and Tank had successfully navigated through an adventure that we had vaguely outlined. We both enjoyed the game, laughed our heads off, and had some great combats, investigations, traps, and a wonderful time getting to play out our characters as much as we wanted. We used a structure to run the game collaboratively, but there were a lot of things that I think actually ‘made it work’ that are less definable.

First, we were both in the same mood. We knew what we were working towards, and we both had a similar idea for the story of the adventure we were going to spin for ourselves. Making characters together helped us prevent an odd couple scenario, and knowing that neither of us felt too serious made sure we didn’t try to take the story in different ways or make it too deep. The lack of seriousness helped a lot. Coming up with the loose and spoiler filled structure at the beginning gave us a framework to work within. In much the same way as improvisational theater and comedy troupes like Second City operate, we walked our characters onto the stage knowing what we were trying to achieve out of the game and were able to act towards that goal without knowing how we were getting there.

I think it also helped that the system did not require a lot of mental investment. Matt had only gotten to see the Numenera book two days earlier, but he picked it up and used the cheat sheets we printed to figure out the rules. With the complexity of enemies and combats being dead simple, we were able to focus on the narrative. Having lots of character options on our sheets though, we felt like we had meaty toys to play with. With our house rules allowing us to modify results after the rolls, we were able to use our characters to their fullest and enjoy the fun powers and gear we had while still taking damage. I think that the “spend your points to modify rolls, but make it damage you in some way” vibe would be something I’d try to carry over.

Ultimately, the best grease for the wheels of our collaboratively run game was trusting the other GM/Player not to screw us over. With equal investment in creating and controlling a fun game, aided by our minimal guidelines that we re-visited when we found ways to improve them, we wanted to make the scenes we ran fun for the other player so that the next scene that they ran was as fun for us. Our ‘reward’ was seeing the other GM/Player take the energy we put into it and build off of that so that we could play out something as fun.

Different Takes

Overall, I enjoyed the collaborative game. I think it works with a specific set of circumstances and might require significantly more investment with a larger group or when attempted with more than a one or two shot. It worked brilliantly for a bit of fun when no one wanted to be the sole Game Master. Thinking about how to make this work for larger groups, I feel that a published adventure could be mined for information and combined with random determiners if a group were okay with spoilers and a brief outline that showed how the adventure should go. An entire dungeon or scenario could be improvised as well, with each player in a larger group taking on 2 or 3 rooms or scenes and handing it off. This tactic would still do well with a general guideline to follow and provide some structure. Players may even take on specific roles, GMing one or two nights with their focus (narrative, the sub-plot, the dungeon, dealing with the council, etc.) being defined and them controlling that story while the other players played it out. They would then lead into the next section and another player would take over with their character being a background only NPC or getting handed off.

I dug our experiment into collaborative Game-mastering and we discussed doing more of it via G+ hangout. I’m looking forward to trying this in different ways and seeing what other games can be turned into games where everyone takes a turn in the GM’s seat. What have your experiences with collaborative Game-mastering been? What pieces of our structure do you think might work for you? What ones would totally fail with your group and what would you replace them with?

Excellent article. I’ve never been involved in a collaborative GMing campaign, but it’s something I’m keen to try out. Plenty of food for thought here.

Thanks! It was a lot easier than I thought it was going to be, but it stayed just as fun. I want to try it with 3 people to see how it goes, then a larger group. I feel like 2 or 4 might be the sweet numbers for this type of game. If you do run something collaboratively, drop a line back about how it went.

My only experience w/ collaborative GMing has been via Cosmic Patrol. With the CosmicP, there actually isn’t a GM so the rules/advice for collaborative GMing are hard-baked into the game.

It’s set up pretty similarly to what you did. There aren’t any huge surprises b/c everyone is going off of the same Mission Brief. Each scene, the role of GM (Lead Narrator in Cosmic Patrol jargon) rotates until the mission brief is done. Of course, each LN’s interpretation of the scene leaves plenty of room for surprises.

(my full review http://violentmediarpg.blogspot.com/2013/07/calling-hq-review-of-cosmic-patrol.html )

I think, in general, for co-GM games to work, the focus needs to be specifically defined (and probably pretty narrow).

Nifty. I’m going to have to check that out. The review you did is excellent as well. I think I saw this at Gencon and it intrigued me then.

Nice detailed writeup. If you get a chance you might enjoy Microscope, which is GM-less. I think the sweet spot 3 or 4 players, but it could work with two. Just like I think the sweet spot for Numenera is probably 3+ and you made it work. It might be interesting to weld Numenera onto the scenes in Microsope… We added a bit of DramaSystem into the scenes and it was interesting.

It’s nice to hear the Numernera rules really are as streamlined as you say. The book is rather large! My first Numenera game will start soon and I’m hoping I don’t fumble too much when I start running it. It’s been *cough**cough* years since I G.M.ed much of anything.

Thanks! I did a review of Microscope a while back and really dug it. Combining something like that with Numenera or the DramaSystem (another thing I reviewed a little while ago) would fill in some of the gaps in a collaborative GMing structure.

Numenera definitely is that streamlined, so you should do fine with it. There are some character creators online that we used to ease through only having one book on us, and there are plenty of resources out there.

There are a couple of things that you can do with collaborative gaming. Rotating GMs is one thing. I really like that you wrote about not being that serious. That’s something that can lock the mind (something said in improv as well) – trying to perform great narrative or awesome descriptions all the time just puts a unnecessary pressure on you. Just relax and contribute in a casual way. (A slight intoxication may help the relaxing.)

Something else I liked was that you were all on the same page. That’s crucial for the game to work. Something else needed is to not plan ahead, because that can lock your mind too. You need a direction but not a planned goal. How things will turn out during the strive against the direction will come as you go.

A third thing that I feel is important with this kind of play is perfect information. You shouldn’t keep anything secret. If your character is a retired assassin, tell the others that so they can create situations around it. If you got a plan with the witch, tell the others that so they wont come up with something that blocks you, and so they wont be unprepared of what’s going on and instead can build on your ideas. Building is a crucial thing with this kind of thing.

You played with rotating GMs, and it’s so common that GM-free normally means that. Games like Fiasco and Polaris are examples this kind of play. There are some other ways of playing, if you want to try out something different.

Distributing the game master’s domain

One participant can take care of monsters, another of setting up intrigues. Example: Archipelago III

One character, several game masters

All game masters have prepared elements on their own that they will incorporate during the session. You need to take the others’ ideas into consideration when presenting your own. One participant plays a character, let say Conan, that the story is formed around. Example: The Coyotes in Chicago

The characters views the world

All participants have characters and the players in the scene must have their character present. Everything established are established from the characters’ eyes. You can perhaps spot an elf, but unless the elf says that it’s an assassin, the character doesn’t know that. Example: Dreamwake

—

One thing that differs the most from traditional play is that it’s usually one story per character. The only exception of all the games that I’ve mentioned above is The Coyotes of Chicago.

I got asked in an email for a more detailed view of how we used the story cubes. Matt and I would roll the dice, then take 3 or 4 that fit vaguely into our ideas. We’d look at the images on them and interpret those.

So, if we were trying to figure out what the NPC would be saying when we asked it about the key, lobster claws on one meant they might know about a monster living there. A mountain on another cube could mean that the thing we were asking the NPC about is in a mountain cave or is a long journey away. Maybe it meant that it was very high up, like on a floating piece of rock. For us, the cubes were just there to give us some ideas when we weren’t sure what to do next. We’d do broad interpretations of the images to spark creativity and get very symbolic about what they meant. Language flash cards or creativity flash cards would be another way to do the same thing.