For the last few years at my local convention, I’ve been running multiple sessions of games that are derived from the original format established by Apocalypse World. If you aren’t familiar with the game, it is a highly narrative game where you map the described actions of a player character to a move. Once that move has been identified, players will roll two six-sided dice and add them together. They may also have a bonus based on stats or other game elements to add to that roll.

This will yield 3 tiers of results. On a 6 or lower, the action is usually unsuccessful, and the person moderating the game is free to introduce a serious complication into the game. On a roll of 7 to 9, an action might be partially successful, or it might be successful, but with an added complication. On a 10 or higher, the action usually succeeds as intended.

This is a very simple mechanic, but there are a number of other elements that shift from game to game that can reinforce a variety of genres and tones. It is this simple base, and the variety of ways to add on to that simple base, that fascinates me. It sometimes takes very few additional rules to give two games with a similar basis a wildly different feel.

I thought it might be fun to examine the games I ran this year, some of the differences between them, and what those additional rules did that made that game feel different from other games with an almost identical resolution mechanic. I’m only going to touch on one or two of the unique mechanics of each game, but most of them have more unique elements than I’m outlining here.

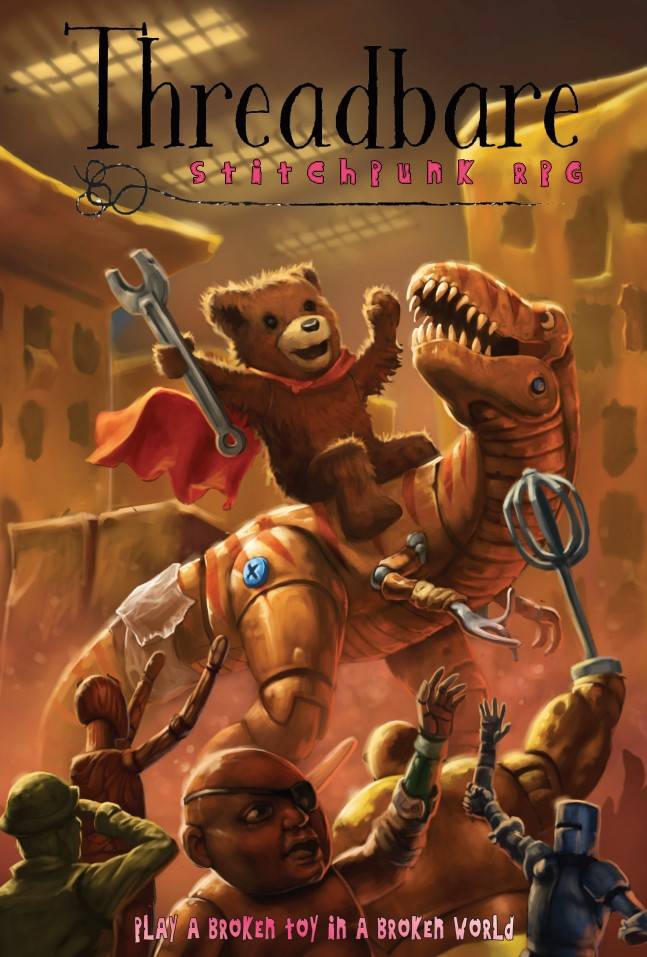

Threadbare

Threadbare is a game by Stephanie Bryant, which I summed up to my players as “post-apocalyptic Toy Story.” Humans are gone, toys are self-aware and ambulatory, and the game examines what their world would look like.

What’s Different About It?

Many games that are inspired by Apocalypse World have playbooks, which are character sheets that have some specific moves to reinforce an archetype that exists in that setting. Threadbare has broader playbooks for different types of toys, with players making choices to narrow down exactly what they are. A Mekka is a hard-plastic toy, but there are variations under this playbook to be a single action figure or a handful of army men.

To further customize the character, a player has a certain number of parts that comprise their toy. They decide what those parts are when they make their character, and parts can become broken over the course of play.

How Did This Affect the Game?

The focus on parts and parts becoming broken affected a lot in the game that I ran. The description of what parts were damaged and how rapidly changed our bright and sunny “living toys” game into a game about the horrors of survival in the outside world. It also meant that the players spent a lot of time talking about their existing parts, giving a vivid visual description of the characters participating, and about what parts they may be using to repair or replace broken parts.

As a default, the game has three different tones, ranging from light and kid-friendly, to dark and adversarial. Our game leaned heavily towards the latter, in large part because of the narrative elements introduced by the description of various parts by the players.

Bedlam Hall

Bedlam Hall is a game by David Kizzia and Monkeyfun Studios, that has been described as “Downton Abbey meets the Addams Family,” with players taking on the roles of staff to a family with various mundane and supernatural troubles.

What’s Different About It?

In addition to managing the troubles of the family, the group also gains and loses prestige, and can trigger Cruel Moves, broadly destructive moves that can affect the household in a broad manner.

How Did This Affect The Game?

When my players failed to contain the growing trouble of the head of the household, he led a ritual that caused the estate to fall outside of time and space. Concerned that the grounds might never return to the Earth, and interested to see if they could trigger an “Elder God versus Demon Lord” fight, one of the players triggered their Cruel Move, and provoked the youngest member of the family, a psychic girl who was attuned to an extra-planar entity.

This caused the household to shift from outside of reality to Hell, and led to the game being wrapped up with a visit from a mister Satan, a foreign dignitary of some renown who was not at all interested in having a British consulate appear on his doorstep. The ability of the players to trigger these Cruel Moves allowed them to wildly and dramatically swing the narrative in a different direction.

Legend of the Elements

Legend of the Elements is a game by Max Hervieux, that emulates a very specific animated style of wuxia that is best identified by Avatar the Last Airbender or the Legend of Korra.

What’s Different About It?

The game rewards players with Chi, which they can use to modify dice rolls or advance their characters. When Chi is used to modify dice rolls, the player running the game can spend that Chi to introduce new elements into the plot.

How Did This Affect The Game?

My first comment on this topic is that the game clearly states that when running a one-shot game, you can ignore the Plot Track mechanic. Me, being someone that can’t help but play with new mechanical toys, still used it for this one shot, to give me an idea of how it works.

This caused me to think about hard moves and plot complications in a different way than I would normally think of them when running a game like this. I had to separate complications that lived “in” a scene, and complications that would lead “out” of a scene. I designed the scenario to have an introductory scene and a large “resolution” scene. I was hoping that both were broad enough that they would be interesting if no one ever spent Chi.

Essentially, the players would be introduced to a problem, go to the source of the problem, and negotiate for the end of the problem. If I could introduce more scenes, there would be scenes where another group would attempt to solve the problem and make it worse, strife would come about between multiple parties, and there would need to be a secondary resolution to maintain the peace even after the negotiation happened.

Eventually, a lot of Chi was spent, and it was weighted towards the end of the session, which caused us to have a slow build and a rapid, increasingly complicated resolution. The session went over well, but it felt strange to me to give up some of the pacing, not just to the players, but in some part to randomness, since the players were rolling a lot of 10+ results at the beginning of the game. Even more than usual, I had to have ideas for scenes that could slot into the story that were ready to go but weren’t attached to the current narrative. It definitely made me wonder how this would work with a longer story arc that played out over multiple sessions.

Even More Games!

So far, I’ve contemplated the first half of the convention. In our next installment, I’ll look at how the rest of the convention games went, and how the different mechanics in those games tilted the game in different directions as well.

Thanks for following along on this analytical journey. If you have any thoughts about similar games that you have played, and how individual mechanics helped to highlight different genres or tones, or even if you just like to use conventions as a test bed to run new games, let me know. I’d love to hear from you.