Every so often, when watching made for television movies, certain character names will pop up, and it becomes obvious that the creative team is attempting to make their version of a Jane Austen story. My wife, daughter, and I have turned this into a game, where we guess what is coming next, and end up rating the moving on how well it actually seemed to be a retelling of a Jane Austen story, versus someone that liked recycling names for their film.

If you have ever played this game while watching made for television movies, take heart! There is no reason to play that game, when there already is a Jane Austen RPG available. Today, we’re going to look at Good Society – A Jane Austen RPG.

The Place Setting

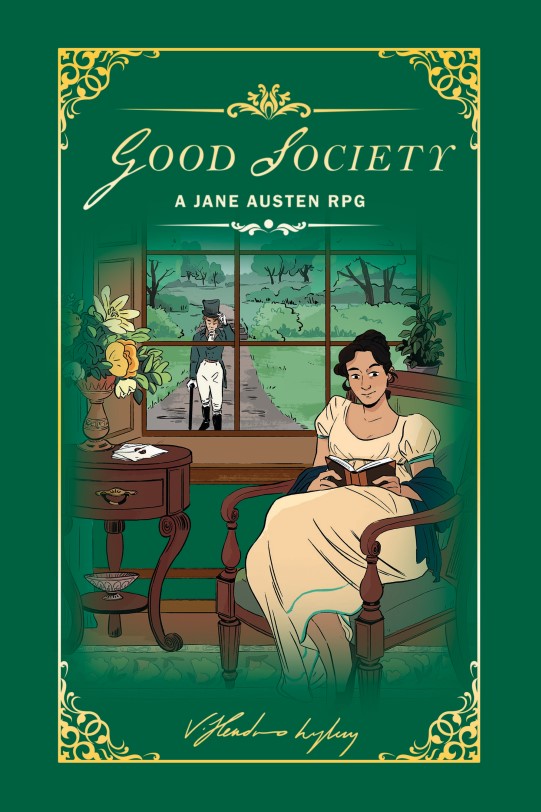

This review is based on the PDF version of the product, which is 280 pages. This includes a three-page glossary and a three-page index. There are page references that exist as sidebars to the main text, as well as various illustrations and flourishes that recall Regency era decorations. One thing especially noteworthy in the artwork – while the art portrays many different Regency era scenes, from dances to picnics, the characters depicted are much more diverse than you might see in most film adaptations of Austen’s work.

The book contains several images showing the cards that can be used with the game. It is possible to play the game just using the rulebook, but generating some of the elements that come from the cards takes a bit more setup time, and if I get this game to the table, I’m definitely investing in the physical decks.

The cards are included as print and play PDFs with the PDF purchase of the game. There are printer friendly versions that are mainly text, and more artistically rendered versions. The characters that appear on the connection cards are as diverse as the characters seen in the various scenes in the rulebook.

Chapter One: Overview

Much of the information about the game as a whole is contained in this opening chapter. In addition to discussing the concept of collaborative storytelling, this chapter also explains the roles of people participating, including the differences between the players and the facilitator.

The game can be played without a facilitator, and while that is touched on in this chapter, there are more guidelines for this style of play later in the book. It is probably fair to say that the facilitator is less like a game moderator for some games, and more like someone that is performing part of the role that the players perform in order to be free to play extra characters and help keep the game on track.

The game has the following cycle of play:

- Novel Chapter

- Reputation

- Rumor and Scandal

- Epistolary

- Novel Chapter

- Reputation

- Epistolary

- Upkeep

The characters primarily portray Major Characters, and those characters have a Character Role Sheet. If you have seen a game like Apocalypse World or Blades in the Dark, the concept is similar, although there aren’t any statistics used to determine success or failure. Instead, the Character Role Sheet explains what defines the character, sets up a list of actions to track for a character’s Inner Conflict, and has a list of actions to check in the Reputation phase to see if a character has gained a positive or negative aspect to their reputation.

Characters have connections, which are played by other characters. They give out relationship cards, which define the connection between two of the player characters, and they have a secret desire, which may be kept secret from the table, although the only requirement in the game is that it is a secret from the other characters to start.

Each character has a number of resolve tokens, including characters connected to the Major Characters, which can be spent to accomplish something they want to have happen. In addition to the resolve tokens, each player has a Monologue token, which they can play on another player to have them explain their inner monologue about a current scene.

There are tips for what aspects of the game to emphasize for shorter games versus longer games, as well as some information on what might be helpful for an online game versus an in-person game.

Chapter 2: Collaboration

Chapter 2: Collaboration

There is an entire section on how the group should work together to establish tone, the degree of historical accuracy, gender roles, hidden information, and topics to avoid. This section also encourages the use of an active safety tool at the table, such as the X-Card.

Collaboration is especially important, as some of the rules involving negotiation and the Playsets require players to be able to agree on moving the narrative forward. This section also mentions that race was not a major factor in Austen’s work, but gender issues are, and that the party needs to be clear on how they are going to handle this.

I’d argue that any people of Roma ancestry might take exception to the concept that Austen’s work was without racial component, given the scene in Emma where they are used as a threat to be run off by Frank Churchill, but I understand the concept that a deep exploration of race and ethnicity in Regency England isn’t what this game is designed to explore.

If you have read enough of my reviews, you know I appreciate when a rulebook will just explain things like tone, and speak frankly about safety, so I appreciate this section.

Chapter 3: Backstory

Backstory goes into more detail on the process of setting up the Major Characters. The first step towards this is selecting a Playset, which is detailed later in the book. This is important because the various Playsets determine what Character Roles are available for play, as well as establishing what kind of story is going to be explored.

The process for setting up the game and the characters is as follows:

- Set up your playset

- Choose desires

- Form relationships

- Choose roles and backgrounds

- Flesh out the major characters

- Introductions

It is interesting to note that you will be picking your desire and establishing relationships before picking the Character Roles and Family Backgrounds. That says a lot of the importance of desires and relationships, versus other details.

Desires sometimes have a public element, and sometimes modify your mandatory relationships, as well as instructing you to share something that is public information. Relationships define one player as the giver and one as the taker, and explain how each of those roles is expressed in the relationship.

Because of all of this, the chapter stresses that this process should be collaborative. Given that some relationships or desires might call for potential romances to be played out, or other emotional connections, like familial bonds, it’s important that everyone agrees that they want those elements in the game.

Characters create connections, which are affiliated characters other than the Major Characters. While they are not Major Characters, they each get their own pool of resolve tokens. The book stresses that these characters exist to be tools of the Major Characters, or to be foils. They aren’t spending these tokens to become the focus of the narrative.

Chapter Three: Rules of Play

Chapter Three: Rules of Play

This chapter goes into more detail on exactly how the resolve tokens work, how reputation is established and used, how inner conflict works (and when it should be used), inner monologues, and how connections should be used.

Resolve tokens are used to shape the story in the direction that the character using that token wishes it to go. There are some guidelines for what requires a token to be used and what doesn’t. Taking general actions that don’t conflict with anyone else, and don’t change the current narrative are just things that you establish when the scene plays out.

Getting private time with a love interest, or learning information about a rival, however, is a major development. If the narrative element you want to introduce into the story affects another character, you have to negotiate with them. Instead of just spending the token, the player pays the other character the token if they accept it. They may refuse, and the new element isn’t introduced into the story, or they may negotiate, and ask for additional narrative elements to happen as well as what the first player wants.

In the Reputation phase, characters may get positive or negative tags based on what has happened in the story and their Character Roles. These tags can be spent by others like resolve tokens if the reputation has something to do with what the character wants to accomplish. If a character gets enough reputation tags, they get a reputation condition, which is in effect until they fall below their tag threshold.

The conditions are story elements that vary based on Character Role, but might include things like being barred from visiting a certain estate, or having an especially strong bond with one of your connections.

Inner Conflicts are noted as being used in games that will be running for multiple cycles. After the first cycle, the character determines their inner conflict, and checks off boxes beneath it when reflecting on their actions. This allows them to gain more resolve tokens, and if a character fully resolves their inner conflict, they can take an Expanded Backstory Action, which is explained in the Cycles of Play section.

The chapter wraps up with the importance of the Monologue Token, which must be played in the Upkeep phase if it was not played before, and the role of Connections, reiterating that they are to be complications or tools, not the primary focus of the narrative.

I am increasingly a fan of narrative currency in games, and I am very interested to see a game based entirely on narrative currency. I know this isn’t the first RPG that has done it, but I particularly like how the economies work, and how tags can be converted.

Chapter Five: Cycles of Play

Chapter Five: Cycles of Play

Cycles of Play revisits the concept introduced earlier in the Overview section, and gives more details on how each section of the cycle works, and how the rules might be modified depending on how many cycles you plan on playing. It also gives the players some ideas on how to place their game, and what each cycle should be about based on how many cycles the game will go on.

Following the steps, characters will determine what they want to see happen in the chapter, determine what type of chapter it will be, and generally outline the chapter before they start play. Example structures include events, visitations, or split scenes.

Events revolve around big social happenings, while visitations involve characters meeting in smaller groups, and split scenes involve a novel chapter where characters start in different types of scenes that are occurring at the same time. There is a comprehensive list of suitable events in case players have a hard time coming up with a suitable idea.

The Reputation phase is where the character looks at what they have done and what the criteria on their Character Role sheet says, and adds tags as indicated. The Rumor and Scandal phase is where players make up rumors, or chose to spread a rumor. A rumor that is spread has it’s own resolve token that can be spent when it makes sense, instead of using a player token, but a rumor that isn’t spread by the next rumor phase doesn’t have any traction.

In upkeep, characters determine if they are keeping their desires or if the desire has been played out, and the various currencies may refresh at this time as well.

I like clearly defined structure in games like this, but my favorite aspect of this is probably the Rumor and Scandal phase. It is a way to keep the world moving outside of the individual scenes, but the rumors aren’t necessarily started or spread by the characters, it is just the players adding their narrative input into what rumors and scandals they want in the game. It is a strong rule to pull players from the character level view of the story to the meta-level, and give them mechanical input into the world development.

Chapter Six: Facilitator

This section lays out the responsibilities of the facilitator, and makes it clear that while you have some ability to play connections and drive the narrative with your own resolve tokens, you are much less of a storyteller in this game than in others.

Not unlike Apocalypse World-derived games, there are principles for the facilitator, and several lists of questions to refer to whenever the facilitator might want to help flesh out a scene or come up with more ideas for the ideal amount of detail.

Advice is also laid out for first sessions, longer games, and short games with less than three cycles. There are tips on games with fewer players where the facilitator might play a major character as well, as well as some rules changes for games that may be run without a facilitator.

Chapter Seven: Playsets

Playsets define the style of story that will be used, and give more precise indications of what exact desires, relationships, roles, and family should be used in the game. For each playset, there is a different list based on the number of players, ranging from three to five, and they include an extra set as a spare, in case players want a little more choice.

The playsets are divided into two groups.

Tonal Playsets

- Farce

- Romantic Comedy

- Drama

Thematic Playsets

- Romance and Love

- Scandal and Reputation

- Rivalry and Revenge

- Family Matters

- Wealth and Fortune

- Obligations

The chapter provides some details on what kinds of stories might develop from the different playsets, and also calls out when it might be suitable to use a given playset. For example, the Farce is noted as being a good playset for games with less than three cycles, new players, or groups that have a hard time maintaining a dramatic tone.

For some of the playsets, there is an event that is assumed to happen after a set number of cycles to change the direction of the story, such as the death of a family member. There are also guides for what playsets have older or younger characters, or a mix of generations, and how that affects the story.

Chapter Eight: Roleplaying in Jane Austen’s World, and Chapter Nine: Characters

Roleplaying in Jane Austen’s World gives several major themes of the stories, as well as some of the items that players should be aware of their characters knowing about the setting.

The Characters chapter breaks down each of the Character Roles, giving examples of characters from Austen’s novels that inspired the role, explains some key concepts associated with the role, and delves into what kind of connections they would have, and how they would view those connections.

Chapter Ten: Knowing Austen

This chapter is a crash course on Austen’s broad themes and setting for players that may be interested in the game, but unfamiliar with Austen’s work. It delves into where the characters live, what they do, what level of formality accompanies different events, and then moves into the more narrative aspects of Austen’s work.

Tropes and plot twists are laid out, so that players will know what kinds of surprises and scandals they should be playing towards.

There could have been no two hearts so open, no tastes so similar, no feelings so in unison The tools for playing out dramatic scenes are so strong that I think a lot of roleplayers would benefit from at least understanding the flow of the game and how it does what it does.Â

This game has so many tools to prompt a player to be proactive and shape the narrative, as well as to tools to guide the player to a logical set of actions to take. Because there aren’t randomizers in the game, the narrative currency is important, and the flow of currency between characters is a powerful tool to keep shifting the spotlight around the table. The formal structure of play gives players the ability to zoom out from their character and add in the overall details to make the world more textured, and the Rumor and Scandal phase just feels like it would be so much fun to work with.

None of us want to be in calm waters all our lives

If you aren’t the type of player that likes to use ancillary objects, playing without the cards seems like it would make the flow of the game a little less smooth. Even with the tools provided, some players may not like the high degree to which they are driving the narrative, or the idea that they are using a randomizer to determine success, but spending a resource that they may want to save for later. The specific setting may not be to everyone’s tastes, even if they would be interested in exploring a more drama based roleplaying game.

Strongly Recommended – This product is exceptional, and may contain content that would interest you even if the game or genre covered is outside of your normal interests.

I know not everyone is going to like a more drama focused RPG, and not everyone is going to be a fan of the setting, but the tools for playing out dramatic scenes are so strong that I think a lot of roleplayers would benefit from at least understanding the flow of the game and how it does what it does. I think the game has a contagious enthusiasm and energy about it.

While the materials provided aren’t completely open, any setting where you have a wealthy class of people interacting with one another, where visitations and events are the norm, can probably be simulated rather easily. I’ve already got ideas for playing out a Downton Abbey style game, as well as doing a “behind the scenes” drama using the various noble houses of Waterdeep.

What genres that are more dramatic than action oriented would you like to see represented in roleplaying games? What games exist already that allow you to play out those dramas? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below!

My wife is a Jane Austen fanatic, and is planning to run this game for our group, but it was fabulous that this review dropped /on her birthday/!

Thank you for this thorough review! I’m backing the Kickstarter reprint and can’t wait to play!