The first time I heard about Osprey Publishing, it was regarding their various military history books. Fast forward a few years, and my friend was explaining to me that they had introduced some miniature wargaming rules based around various themes, that were “miniature line agnostic,” meaning they were putting out their own lines of minis, just showing you how you could use existing minis for the game. Then I encountered their line of fantasy military supplements, creating similar books for dwarves, orcs, and elves as they had for real-world armies.

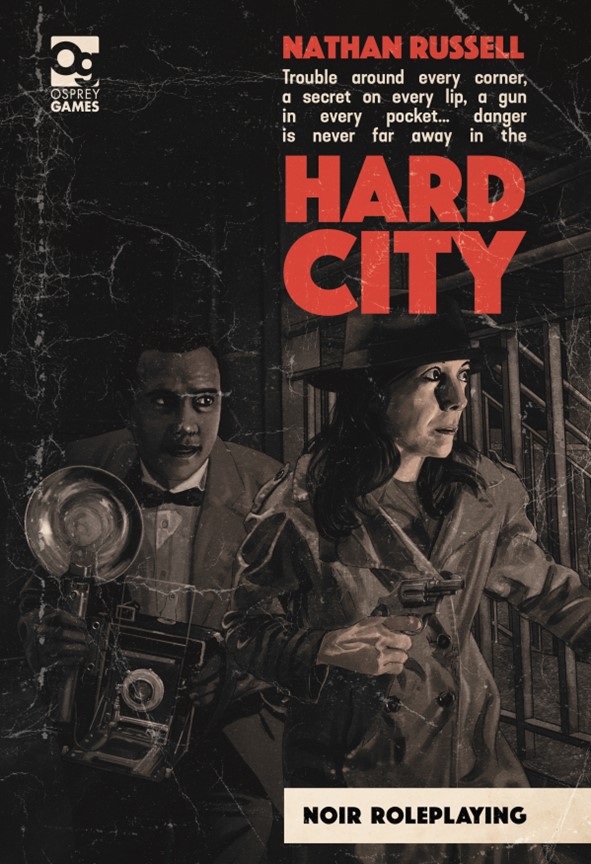

All of this led me to realize that Osprey has been expanding into the RPG market as well. They have published RPGs on British folklore, prehistoric fantasy, science fiction, wuxia, the bronze age, the Knights Templar, cyberpunk noir, and, what we’re looking at today, 1940s-era hard-boiled noir stories. I wanted to get a feel for what Osprey is offering, so today we’re going to look at Hard City.

Disclaimer

I have not had the opportunity to play or run Hard City. I did not receive a review copy of the game, and purchased the game for review on my own.

Hard City

Publisher Osprey Games

Author Nathan Russell

Artist Luis F. Sanz

Layout and Format

The PDF of this product is 161 pages long. This includes a title page, a copyright page, a three-page table of contents, a glossary, a character sheet, and an acknowledgment/credits page. The book is arranged in single page layout, with bold red headers for new topics. Sidebars are simple outlined sections that take up the full width of the page. Each of the chapters has full-page artwork, and there is half-page artwork included on various pages inside the chapters.

The artwork is thematically appropriate for a 1940s-era noir story. In addition to portraying hard-bitten characters in different noir-appropriate situations, there is a diverse range of people in the images, in both gender presentation and race/ethnicity.

Contents

The PDF is divided into the following sections:

- Welcome to the City

- The Basics

- Characters

- Getting Into Trouble

- Hitting the Mean Streets

- Downtime

- The City

- Cases

- Game Master Advice

- Threats

- Case: Engagement with Death

- Case: In at The Deep End

The Rules

At its most basic, in terms of mechanics, Hard City is a game about assembling a dice pool of Action Dice based on the character’s traits, adding Danger Dice based on the difficulty of the situation and complicating factors, and rolling them. Each Danger Die that matches an Action Die cancels that die out, and the highest of the remaining Action Dice is the result of the check.

- 6–Success

- 4 or 5–Partial Success

- 3 or less–Failure

- No Action Dice uncancelled or only 1s remaining–Botch

If there are additional 6s beyond the first, this may allow the PC to add boons to their result. These boons may just be additional positive narrative results, or they may have mechanical weight (for example, in extended tests or in combat). All of the rolls are player-facing, which means if the GM’s characters are taking an action, the PCs are rolling to react to that action, rather than the GM rolling.

Extended Tasks require characters to score three successes before three failures, and might be used for situations like chases or interrogations.

Combat or any more structured scene calls for characters to be sorted into a specific resolution order. Most of the time, this will mean that the PCs go first in each of these phases. There is no check to see who goes first, the PCs just determine what they are doing, get sorted into the appropriate phase of the structured scene, and take turns whenever it makes sense. The structured scene order looks like this:

- Talking

- Moving

- Shooting

- Fighting

Threats all have the same general format, which means you could have a warehouse on fire as well as several goons, and each will be formatted with a series of tags that might serve to help frame how many Danger Dice to add to the pool when addressing that threat, as well as drives and actions. Each of the goons may have one Grit, and the fire might have three Grit, meaning it takes one successful action to remove a Goon from the scene, and three successful actions to put out the fire. Boons generated from additional 6s rolled can be applied to these numbers, so someone getting a boon while putting out the fire may remove two Grit instead of one from the threat.

It’s interesting to see the hybridization of various games going into these rules. It’s not a Powered by the Apocalypse or Forged in the Dark game, but it borrows from both of those, as well as other games like Fate, and even a little bit of the Doctor Who Roleplaying Game.

Player Characters

Player Characters

Player Characters are built by picking a Trademark for their Past, Present, and a Perk. So in your Past, you may have been a Performer, in your Present you may be a Negotiator, and for your Perk, you may be Famous.

You have five Edges that you can arrange under your Trademarks, as long as you have at least one under each Trademark. Whenever you take an action, you gain an Action Die for the Trademark that you are using for that action, and an additional Action Die for each Edge that applies to the action that you are taking.

Each character also takes two Flaws. Whenever a Flaw causes problems for a PC, they get to refresh their Moxie pool. Characters also assign a Drive and Ties, which are used to determine XP awards for advancement.

Each character starts out with a maximum of three Moxie and three Grit. Grit represents the number of injuries you can sustain until you are out of a scene. Moxie is a resource that you can spend to change a die result, remove a Condition, or use a Voice-over to add details to a scene. Moxie can also allow you to use a second Trademark in a check, which could potentially also grant you more dice for relevant Edges under that Trademark.

Conditions are generally gained as consequences for not receiving a full success, and if they are relevant to a particular action, they also add Danger Dice to your pool. Grit represents the number of injuries you can take, but each of those injuries can have varying severity. Injuries can be Light, Moderate, or Serious. You can decide if you want to mark a new injury or upgrade an existing one when the Injury is suffered. You can’t upgrade a Severe Injury. If you don’t upgrade your Injuries, you may be taken out more easily, but are less likely to be dying when you are taken out.

When creating characters, the group is encouraged to come up with a campaign framework that explains why the PCs are working together to do what they do. The suggested frameworks include:

- Wrong Place, Wrong Time

- Private Eyes

- Operatives

- Special Division

Wrong Place, Wrong Time represents regular people who get caught up in a dangerous situation that they have to work through, and is noted as being appropriate for one-shots. Private Eyes assumes the PCs all own their own PI firm, with different PCs having different specializations. Operatives assumes that the group is working for larger organizations as fixers or investigators of some sort. Special Division assumes that the PCs are working as part of a law enforcement task force on corruption.

I like the campaign framework idea a lot, but I wish there were a few more examples or a few more granular subdivisions under each of those. I wouldn’t even mind if the Campaign Framework had its own tags that could be accessed when appropriate.

The Setting

The Setting

Hard City uses a broadly drawn setting known as, appropriately, The City. By default, the starting year of the campaign is 1946, allowing for the fallout of War World II to be factored into the fabric of the story. There are three pages of tables that show some of the common goods for sale and their prices in this era, although the game itself isn’t especially concerned with buying or selling gear or goods.

The highest tier of organized crime is The Syndicate, but several crime families and organizations are mentioned. For example, the Johnsons run Anvil City, and the Sullivan Clan runs Bridgetown, but the biggest family is the Cesares. It’s a little disappointing that the Triad is mentioned as being active in Chinatown, but ends up being less detailed than any other criminal organization in that it has no families or NPCs detailed.

There is a section on personalities of the city, including the categories Movers and Shakers and Troublemakers. Most of these characters get a sentence or two to broadly define their roles in the city.

Various sections of the city get one-page descriptions, usually a few paragraphs each, in addition to a section on places in that district, and tags that can be used to portray that district (we’ll get to tags a little bit later). In addition, each district gets its own set of example hooks, four each, to help explain what kind of stories might relate to what districts.

While not given any specific geographic location, The City is mentioned as having an ocean on one side, hills on the other side, with farmlands and oil fields bordering The City on the other sides. This is a broadly drawn setting to allow for a wide variety of hard-boiled or noir themes, without dwelling on real-world history outside of the broad generalities of the era.

I’m not exactly sure where the best place to put this observation is, so I’ll throw it here in the Setting section, because a lot of what I’m about to say is about how the book presents atmosphere. In the technical sections, when presenting the game as a game, the book does a very good job of reinforcing that the table needs to avoid harmful stereotypes, like those associated with race/ethnicity, gender, or other marginalized identities. However, the thematic use of language reinforces some aspects of the stereotypes of the era, especially when describing women. Gendered terms are used a lot without a lot of text used to contextualize or broaden those terms. For example, “tough guys” and “femme fatales” as different archetypes.

Some of this feels like a consequence of how the book is doing things. When it’s talking about the game as a game, it makes a strong statement, but does so in a very focused and concise manner, but when it is presenting atmosphere, it tends to linger a bit more.

For the Game Master

In addition to the general rules for the game, there are about seven pages of GM advice on how to structure and run a game session. Game sessions are broadly organized into either Investigations or Heists. One of the biggest takeaways in this section is that the GM shouldn’t keep clues locked away from the PCs, and that they should provide more clues than they need to move the plot forward.

The GM section also has a number of threats detailed, each one having the following elements:

- Name

- Drive

- Grit

- Tags

- Actions

As mentioned above, Grit serves the same purpose as it does for PCs, but in this case, you aren’t tracking the severity or assigning specific injuries. It’s just a measure of how many successes you need to remove the threat. The threats in this section are organized into People, Environments, and Organizations. For Organizations, PCs may be in a position to damage that organization and reduce its Grit, and with enough successes, may remove that organization as a threat.

I like framing Organizations as threats in this manner. I can easily picture PCs, after they have dealt with a member of a crime family, doing some research to tie that person back to the organization in question, and moving them “one step closer” to bringing the whole thing down. Not only is it a fun campaign timer, but it also fits very well with themes like a Hard Boiled detective trying to make their name by toppling a major crime figure in The City.

The advice that is here is good. It is advice that someone brand new to RPGs or to this particular set of genre tropes is going to need to make sure they don’t make some major mistakes that spoil the mood. I do feel that it could have used a few more examples to back up those best practices. Admittedly, it’s hard for me to gauge because I’ve read so many GM chapters, and I’ve read a lot of chapters that deal with presenting stories similar to what this RPG is facilitating.

Example Cases

Example Cases

There are two example cases provided in the book. I’m always a fan of example adventures, even if you never end up using them. It shows you what the designers feel is important in an adventure, as well as how to incorporate elements of the game. In this case, there are two example cases, one being an investigation and one being a heist.

The first case involves finding a man who is engaged to be married and has disappeared, and the second case involves artwork smuggled back to the States after World War II and being sold to a private buyer.

I appreciate that the “heist” case has notes on how you can use the heist framework and tropes, but model it on infiltrating the location to gather evidence for a story or a prosecution, as well as just breaking in to steal the artwork. The investigation is definitely steeped in the tropes of the genre, but it’s a good example of what I mentioned above in the setting section.

Let’s look at the tags and actions of the two women that appear in the adventure:

- Gloria Davenport tags: Attractive, Athletic, Charm, Make a Deal, Seduction, Lie, Strong-willed

- Gloria Davenport actions: Fluster you, Distract you, Pay you off, Make a scene, Make you beg for more

- Sylvia Rossi tags: Empathy, Alert, Notice, Always Watched

- Sylvia Rossi actions: Give you a sob story, Spot impending trouble, Spill the beans, Run away

What makes this even more awkward is that Sylvia is an abused wife, and there is a particularly vicious trope that is thrown into the mix as a plot twist.

If nothing else, I would have liked a little more discussion around the intentionality of using these tropes, and if there is a way to engage them with more depth or meaning, instead of just perpetuating stereotypes found in noir or hard-boiled media.

Happy Ending If you want to do the work, it’s a solid foundation

I enjoy how the tag system presents narrative-focused elements and translates them into mechanics for resolution. I think the book makes some good choices in presenting The City as a more abstract setting that is flexible enough to use for multiple noir and hard-boiled stories. I appreciate that you can frame environments and organizations with the same rules as dangerous villains, which gives you more flexibility in framing action scenes than just shooting or punching the opposition.

The Big Sleep

There are two paragraphs on safety, which largely point you toward other resources you can research on your own. While the technical game aspects of the game make it clear that you shouldn’t spend time on the harmful stereotypes of the genre, the presentation of the setting and adventures is somewhat at odds with that message. There could have been more work done to either contextualize and take a deeper look at including and deconstructing those stereotypes, or even building an alternate reality that plays with some of the themes of noir and hard-boiled fiction without others, but instead, the book relies on the GM to do that work on their own.

Tenuous Recommendation–The product has positive aspects, but buyers may want to make sure the positive aspects align with their tastes before moving this up their list of what to purchase next.

Hard-boiled detective stories are one of the genres that I really want to spend more time with in gaming, and I like the foundation that this game lays down. However, it lacks the more intentional engagement with the topics that many of the best modern games include. If you want to do the work, it’s a solid foundation, but you really should do the work to make your game a safer environment, and you’re going to be doing that work largely on your own.