When I watch fight scenes, I often think of the discussions on one of my favorite podcasts, Jianghu Hustle, about how in wuxia stories, the fight is a means of telling a story – an alternate form of dialogue that uses physicality instead of words. Characters are often defeated by an antagonist early in the story to establish scale and the need to get better at what they do. Family members and love interests end up having ties to events that unfold. The way a foe is defeated tells you what kind of protagonist you are dealing with.

While I had watched various wuxia movies in the past, listening to the podcast had me watching along with various movies and looking at them with a better understanding of why those movies do what they do. I watched movies like Iron Monkey, Hero, and House of Flying Daggers, not just to see cool fight scenes, but to look at how fights were paced, what the moves and counter moves said about the characters, and how they advanced the narrative.

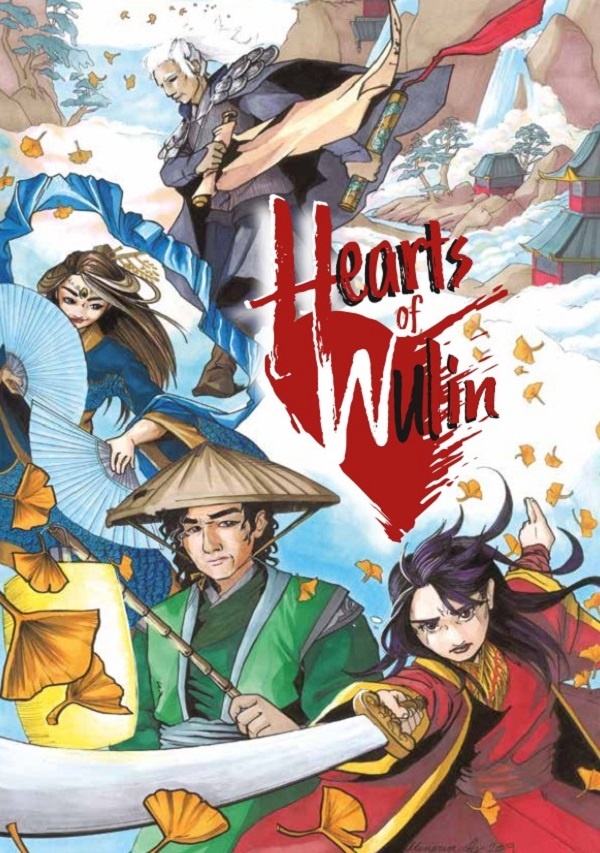

All of this is to say that thinking about the storytelling of physicality, the concepts of scale, and the melodrama of relationships put me in mind of Hearts of Wulin, a Powered by the Apocalypse game that emulates Wuxia stories.

The Unfolding Game

This review is based on the PDF of Hearts of Wulin. The PDF is 231 pages. This includes a credits page, a table of contents, a six-page index, eight pages of Kickstarter backers, and a list of alternative entanglements. In addition to the PDF rulebook document, there are also various play aids available for the game, including a character creation summary, a core moves sheet, core playbooks, courtly playbooks, fantastic moves sheet, and fantastic playbooks, as well as an entanglement sheet for each of these.

We’ll talk more about these later, but the courtly and fantastic playbooks and moves don’t fully replace the core rulebooks or moves but supplement them for different genres being emulated. The same playbooks exist in each style of play, but some moves are added and some are removed, to better incorporate the style of story being presented. I really like this kind of thorough supplementary material because I have seen games in the past that present optional material that doesn’t have the same kind of support that the core options receive.

Who Tells Your Story

It’s worth noting that I’m a white guy commenting on an RPG about wuxia stories. I enjoy the genre, but I am, by no means, an expert either on the culture or the media. The folks at Jianghu Hustle are great, and know way more than I do, but they too, are white guys. So, it’s worth looking at the design team.

This started with Lowell Francis, also a white man, and his love of the media. That said, Lowell realized that he needed additional perspective on the topics, and a broader understanding of the context of cultural tropes. That led to additional development by Agatha Cheng, Jamila Nedjadi, Alun Rees, and Sherri Stewart, as well as picking up an additional writer in Joyce Ch’ng, with sensitivity reading done by Yilin Wang and Agatha Cheng.

Intro, Safety and Content

The introduction touches on the history of wuxia stories, originating with more fantastic stories captured in novels. These gave way to less fantastical stories in the 20th century, where the fantasy became more “heightened reality,” but the longer such stories have been told in visual media, the more that fantastic elements have been expanding again.

This section also describes where Hearts of Wulin resembles traditional Powered by the Apocalypse games, and what it does differently. Much of the unique ground provided by this set of rules exists within the concepts of entanglements, bonds, scale, and elements. The game uses the traditional resolution categories of 6- (miss)/7-9 (partial hit)/10+ (hit), but characters may spend bonds on some roles, elements may change the frame of reference for this resolution, and instead of statistics, characters roll +elements. Those elements are as follows:

- Earth

- Fire

- Metal

- Water

- Wood

Each of these elements has positive and negative traits associated with them. Often, characters are free to choose which element they want to roll with, but it needs to fit the narration of their approach, and some moves cause a character to mark their element, meaning it’s unavailable for use until something specific happens to open that element up again.

Each of these elements has positive and negative traits associated with them. Often, characters are free to choose which element they want to roll with, but it needs to fit the narration of their approach, and some moves cause a character to mark their element, meaning it’s unavailable for use until something specific happens to open that element up again.

Each character has two entanglements, usually framed as incorporating the PC, another PC, and an NPC. For example, a romantic entanglement may have a PC drawn to the betrothed of another PC. Whenever this conflict comes into play, there is a special move that can be rolled representing the character’s inner turmoil.

The safety and content section includes a discussion of session zero procedures to set expectations, determining what can and can’t happen in a story at the table, and using active safety tools. There is also a discussion on dos and don’ts regarding an existing culture, diving into topics like cultural appropriation and respect for other player’s lived experiences.

Character Creation, Basic Moves, Conflicts and Advancement, Entanglements, Playbooks

Character creation involves picking a playbook, assigning numbers to your elements, picking your initial moves, and creating your entanglements. Much of this will feel familiar to players if they have created characters in other Powered by the Apocalypse games. The playbooks for this game are:

- Aware

- Bravo

- Loyal

- Outsider

- Student

- Unorthodox

While six playbooks are enough to facilitate most playgroups, the playbooks have another means of specializing the exact “type” of that playbook a character is playing. Each one of these playbooks has three “role” moves that further flavor the archetype of the character, in addition to the two starting moves that a character picks from the general playbook moves.

While six playbooks are enough to facilitate most playgroups, the playbooks have another means of specializing the exact “type” of that playbook a character is playing. Each one of these playbooks has three “role” moves that further flavor the archetype of the character, in addition to the two starting moves that a character picks from the general playbook moves.

Each individual playbook has specific wording for its general and romantic entanglements. Characters that don’t want to have a romantic entanglement can take a separate general entanglement, and those entanglements help to create an extended cast of characters for the game. Characters also have bonds with specific characters, and these bonds can be spent to affect rolls, using the strength granted by the bond to help the character focus on succeeding in their tasks.

There are basic moves for assisting other characters (which can clear marked elements or create new bonds), impress others, deal with inner turmoil, gather information, or deal with adverse conditions. There are also separate moves for when a character fights a duel, fights troops of an antagonist, or fights against another PC.

All these resolutions are dependent on scale. If an opponent is lower in scale, the stakes of the check are much lower, and the PC will always win – but with different secondary effects. PCs will always lose against someone with higher scale, but again, with varying effects based on how well the roll goes. If you want to learn how to become better to face that opponent on equal terms, that may take teamwork, or for you to engage the move that allows you to learn new techniques.

PC versus PC duels are interesting, in that they are resolved through meta-negotiation. The initiator of the fight offers the other player something, and if they accept, their character loses the fight, but gains what was offered.

Characters advance at 8 XP, and they gain XP from taking a loss in conflict, rolling against their inner conflict, or interacting with their entanglements. One entanglement per session will be highlighted, so it’s the one the PC wants to see come into the forefront and is worth an extra XP.

As an aside, I’ve never been a fan of highlighting abilities in PbtA games, but I really like the idea of highlighting an entanglement. This is a direct comment to the GM about what the PC wants to interact with most.

Gamemastering, GM Moves, GMing Playbooks, Scenario Starters

The gamemastering section does what you might expect in a PbtA game, establishing principles and agendas, but as with the previous sections, the language feels more natural than some of the “first generation” PbtA games.

The examples for hard moves and soft moves (the moves made by the GM when a character rolls a 6- as a result) did surprise me a little. I’m used to soft moves being more narrative “heralds” of something that’s about to happen, but both hard moves and soft moves, in the examples, have instances of specifically engaging with rules content.

There is also a discussion of how to adjudicate the moves in the game. This includes making some open-ended results less so in some situations, as well as modifying how some moves work if the XP triggers occur too often for your tastes. This section also presents an extended duel variant, including a Face-Off and Concentration phase before the final clash.

There are 36 scenario starters (one for each chamber of Shaolin, according to the Shaw Brothers) to inspire game masters. I’m just going to say right now that I love these. There are some great ideas in here, many of which are drawn from some classic wuxia stories. These starters include lost scrolls of power, framed Heroes, tournaments, and mysterious invitations.

Courtly Wuxia, Fantastic Wuxia

The next section of the book deals with subgenres within wuxia stories. Courtly wuxia deals with characters that must navigate politics and noble families, as well as other conflicts. Fantastic wuxia involves wuxia stories that heavily involve monsters, gods, magic, and supernatural elements.

Instead of creating entirely new playbooks, each subgenre introduces an additional role suited to the subgenre being discussed and indicates several moves from the standard playbook to be swapped out with other moves specific to the genre. I’m normally someone that likes PbtA games to have lots of variety in playbooks, but I really like how this game deals with customization of the core six playbooks for different situations.

Characters in a courtly setting have additional moves, like The Game of Court, and the Social Duel. Players have access to a new narrative currency, Influence, which is used with some of the new moves. Characters pick an agenda for their characters, and conflicts with their agenda can trigger the character’s inner turmoil as well.

Characters in a courtly setting have additional moves, like The Game of Court, and the Social Duel. Players have access to a new narrative currency, Influence, which is used with some of the new moves. Characters pick an agenda for their characters, and conflicts with their agenda can trigger the character’s inner turmoil as well.

In addition to these courtly maneuvers, there is also a set of moves for resolving mass combat. These either involve characters performing a major deed that turns the tide of battle or involves characters “wagering” what is at stake in the battle and rolling to see how many of those items at stake must be sacrificed for a victory.

The Fantastic Wuxia section introduces moves for Facing the Supernatural, Seeking Experts, Using Found Magic, and Uncovering Banes. Additionally, it creates some supernatural traits that monsters and other creatures might have that could affect the PCs engaging them. For example, an undying creature may be defeated, but will always come back if its bane isn’t discovered. A venomous creature keeps a character from clearing a check on an element until some supernatural solution is applied.

While there are a lot of new roles for characters in both genres, I wanted to specifically call out the Unorthodox Playbook’s supernatural role “In Human Guise.” This really underscores the flexibility that these roles provide in changing the context of these archetypes because this allows the Unorthodox to be a supernatural creature themself.

History & Cultural Notes, Setting Alternatives

This section opens with a timeline of historical dynasties in China, and touches on various historical elements that are often included, in some form or another, in a wuxia narrative taking place in historical China. These include topics like the Emperor, philosophies and religions, codes of behavior, and the Shaolin temple, including how wuxia stories often deviate from the actual historical Shaolin temple.

There is a list of settings that can be used for wuxia stories, as well as the types of stories that work well in those alternate settings. These include themes like detective stories, adventures, heists, and science fiction twists. All of these include discussions on how those types of stories take on different trappings when associated with wuxia stories.

One genre I was hoping to see involved modern stories and crime dramas. Probably because I really like Fonda Lee’s novels. That said, there is a lot of guidance on making different campaigns in this section.

Narrative Fight Scenes

Remember when I was talking about Jianghu Hustle? This section of the book is by those podcasters, discussing in more depth what specific actions can say in the narrative of the game. Because the game itself generally resolves conflicts with a single roll, much of this chapter is about narrating what an extended fight might look like before going to the results of that role to wrap up the narration.

Greater Scale This game hits on multiple levels. By itself, it is a strong game to engage with the various genres and subgenres of wuxia.

This is a great PbtA game for presenting the rules with natural language that is both understandable and engaging. It covers the topics in a comprehensive but succinct manner, and it covers a lot of ground. I was honestly surprised at how comprehensive the sections on courtly and fantastic wuxia were, as that’s the type of material I usually expect to see in the supplemental material. Almost every time I thought to myself, “I wonder how I would do this in the game,” the answer was usually in the next section that I read.

Marked Element

I don’t see too many downsides to this game. There are a few references to other games and rules that can be used to emulate optional items that I’m not sure were fleshed out enough for anyone that doesn’t have those rules. I might have wanted a little more information on “crossing the streams” between courtly and fantastic wuxia (for example, in a setting like Ice Fantasy).

Recommended–If the product fits in your broad area of gaming interests, you are likely to be happy with this purchase.

This game hits on multiple levels. By itself, it is a strong game to engage with the various genres and subgenres of wuxia. It includes a lot of solid advice and information for anyone that may run wuxia-style adventures with other game systems. It does some solid work in the PbtA design space, highlighting flexibility and compact design. Any of those reasons will make this a solid purchase.

What are your favorite genres from various media to see translated into games? What makes for good genre emulation? Would you rather have a game that broadly emulated a genre, or one that specifically models an existing IP? We want to hear from you in the comments below!