Critical Role has evolved quite a bit in the last few years. Not only is it a wildly successful streaming show, but the members of the show formed their own company. This company rapidly moved into comic books, prose novels, and a whole range of other products. In conjunction with Green Ronin, they published a campaign setting book, and then began to produce official D&D products in conjunction with Wizards of the Coast.

The next phase of this evolution came with the creation of Darrington Press. Darrington Press was the game arm of Critical Role, originally publishing board games based on their IP, but eventually moving into publishing RPG material. When the second version of the Tal’dorei setting book was released, it wasn’t through another company, but was a product of in-house development from Darrington Press.

While Darrington Press was already poised to expand their RPG offerings, quite a few eyes shifted towards the company when WotC began rumblings in January of 2023 that they were going to go back on a 23-year-old promise to make the Open Game License, well, open. Was Critical Role going to create their own RPG? The answer was yes, but also, it’s complicated.

Darrington Press’ plan was to produce a story arc-based RPG, made for “seasonal” play, and a game meant to facilitate long term campaign play. The narrative seasonal game would be using an engine known as the Illuminated Worlds system, while the campaign length fantasy game would be published under the name Daggerheart. It turns out that the Illuminated Worlds system would be used for different settings, and what we’re looking at today is the first game to use that underlying game system, Candela Obscura.

Disclaimer

I was provided with a review copy of the game from Darrington Press, and I have received review copies from the company in the past. I have not had the opportunity to run or play this game, however, the Illuminated Worlds system is derived from the Forged in the Dark rules, which I have run and played multiple times. That said, this is a unique iteration of those rules.

Candela Obscura Core RulebookLead Game Design: Spenser Starke And Rowan Hall

Written By: Rowan Hall And Spenser Starke

Editor: Karen Twelves

Managing Editor: Matthew Key

Production: Ivan Van Norman And Alex Uboldi

Proofreading: Jacky Leung Additional

Game Design: Christopher Grey, Tracey Harrison, And Taliesin Jaffe

Layout: De La Rosa Design

Cultural Consultants: Basheer Ghouse, Pam Punzalan, Erin Roberts, Christine Sandquist, Liam Stevens

Military & Political Consultant: Anthony Joyce-Rivera

Game Development Consultant: Mike Underwood

Additional Editing: Darcy Ross

Additional Writing: Carlos Cisco, Tracey Harrison, Anthony Joyce-Rivera, Sam Maggs, Mike Underwood

Graphic Design: Aaron Monroy, Bryan Weiss Artists: Shaun Ellis, Jamie Harrison, Allie Irwin, Amelia Leonards, Lily Mcdonnell, Justin O’neal, Sunga Park, Gustavo Rodrigues Pelissari, Doug Telford

Map Design: Marc Moureau

Cover Artist: John Harper (Deluxe) De La Rosa Design (Standard)

Artist / Ancient Languages / Spell Design: Stevie Morley

Original Concept Created By: Taliesin Jaffe and Chris Lockey

Illuminated Worlds System Design: Stras Acimovic and Layla Adelman

Illuminated Worlds Preliminary Design: Daniel Kwan, Eloy Lasanta, Matthew Mercer

Format

I was provided with a copy of the physical book for this review. When I started the review, the PDF was not available, but I did pick up the Demiplane version of the rules to facilitate revisiting various sections. The physical book is 204 pages long. This includes a title page, a credits page, a table of contents, a two-page summary of rules, and a two-page index. The physical book includes a green cloth ribbon bookmark.

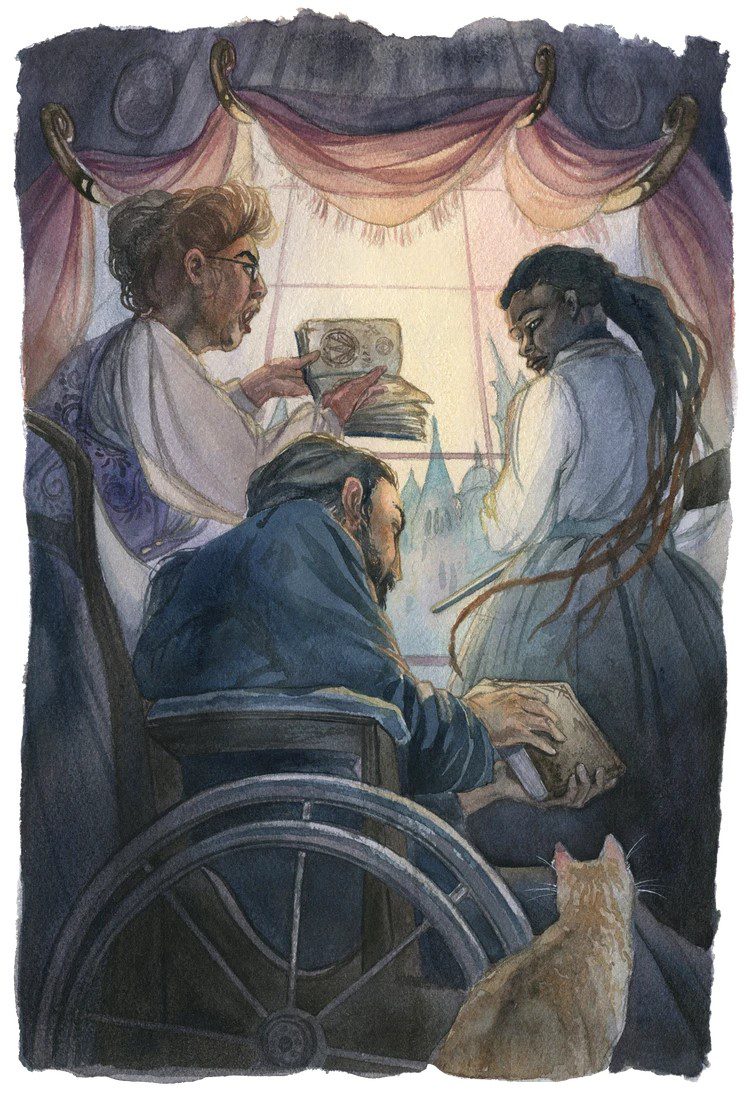

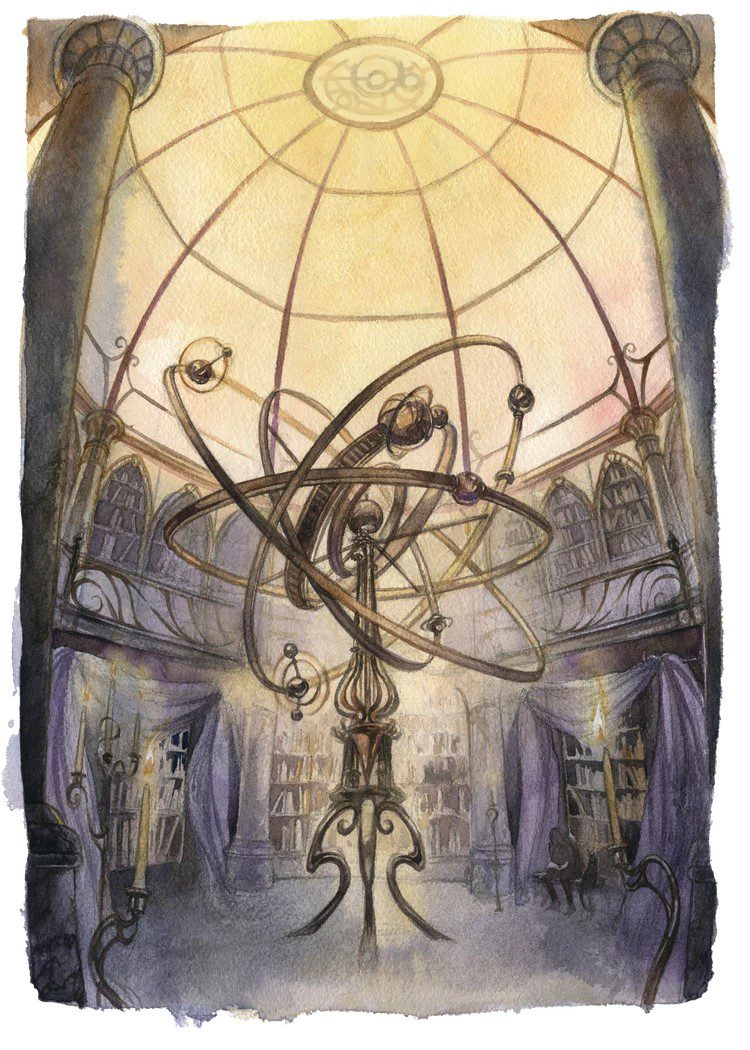

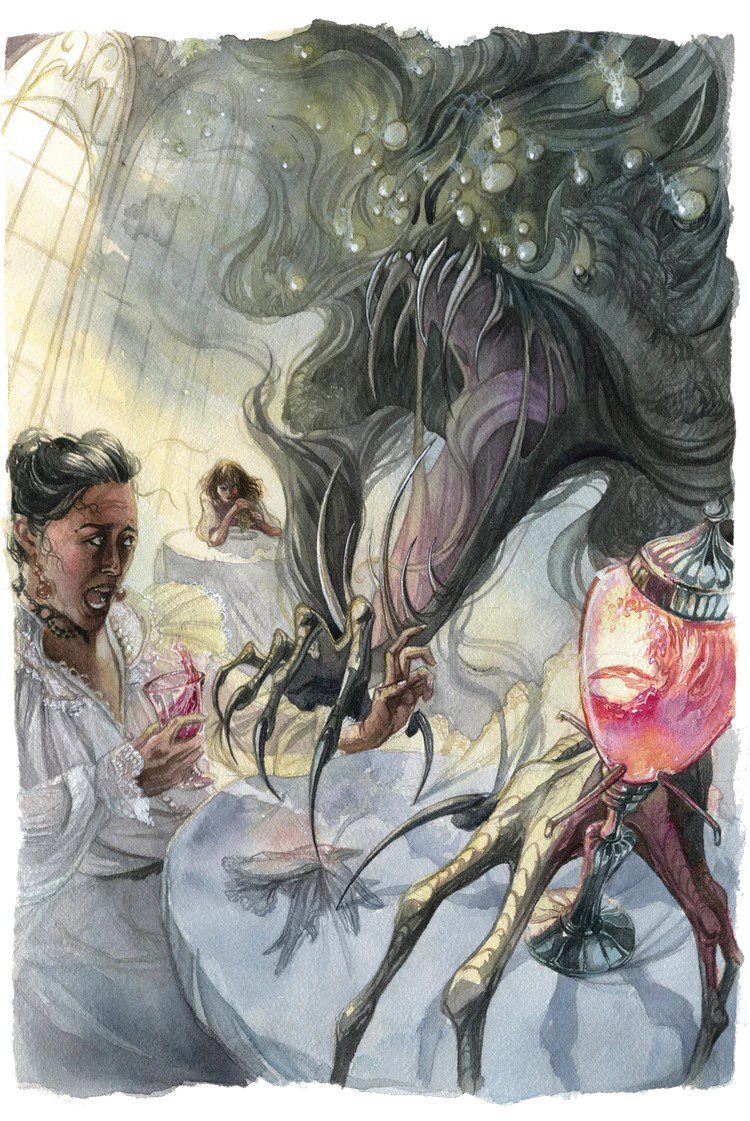

The pages are thick, glossy stock, and there is a combination of color artwork and line drawing. In addition to the art pieces, there are many “artifacts” included in the book, such as reproduced letters and newspaper clippings. The chapter introductions are full page, full color artwork. The cover (which is the standard cover) is a black glossy cover with an embossed representation of the concentric rings of an orrery. The lettering is called out in a muted gold tone.

A Different World

A Different World

Candela Obscura is a horror RPG, where your characters are investigating supernatural phenomena and creatures. It is set in an alternate world that has some similarities to our world but breaks apart some elements and reassembles them in a different way. For simplicity’s sake, the year in the setting is 1905, and this is meant to be a signal as to what historical touchstones are at play in the setting, by looking at what was in play in 1905 in the real world.

The primary setting of Candela Obscura is the city of Newfaire, in the region known as the Fairelands. The Fairelands are part of a larger coalition known as Hale, and Hale was, until very recently, embroiled in a war with the nation of Otherwhere across the sea. This war ended with the use of an electrical device causing widespread devastation and had a cultural impact like the atom bomb in real world history.

Newfaire is built on top of the ruins of Oldfaire, which was the capital of an ancient empire. There is a lot of archeological work done in the ruins of Oldfaire, which is far more preserved than it should be for the length of time since its passing. Part of this is because Oldfaire delved deeply into the use of magic.

Magic is known in the Candela Obscura setting, but it’s known as a damaging force that leaks into reality, wreaking havoc in its wake. In general, the people of the setting don’t view magic as a source of wonder. The process of magic seeping into the world is called Bleed, which flavors how magic is treated in the setting.

Candela Obscura is an ancient society that can trace its roots all the way back to Oldfaire. Its core tenet is to keep people safe from dangerous magic, closing supernatural Flares, mitigating the harm created by supernatural creatures, and hiding away magical artifacts where they can’t be used. Candela Obscura doesn’t have official standing in the governments of Newfaire or Hale, but the members of the organization have plenty of connections and infrastructure, and sometimes even official organizations defer to their expertise.

The setting is meant to be an Edwardian-styled investigative game, where the PCs still must navigate the Ascendancy (the church), the Primacy (the government), and the Periphery (the police). All these organizations respect the dangers of magic, but corruption and intolerance can complicate investigations. For example, the Periphery may want to deal with a supernatural outbreak in a neighborhood by razing it to the ground and disappearing the residents.

Where you have one esoteric organization, you must have equal and opposite esoteric organizations. The following organizations all exist to make the lives of the members of Candela Obscura more interesting:

- The Exoteric Order of New Sciences (Scientists that want to harness occult power to push the boundaries of technology)

- The Office of Unexplained Phenomena (the section of the Periphery charged with dealing specifically with the supernatural)

- The Pyre (a sect of the Church of the Ascendancy that wants to deal with anything supernatural by burning it to ashes)

- The Red Hand (an organized group of traffickers of supernatural artifacts)

- The Unabridged (a loosely organized group of humans that have discovered immortality and often infiltrate other organizations)

Candela Obscura builds structures known as lighthouses to mark areas where a flare cannot be contained. Inside these lighthouses exist astrolabes that are built to redirect and contain the flares so they don’t spread. Candela Obscura also has a 13th Warehouse . . . no, wait, a Fourth Pharos, the fourth centralized structure that the organization has constructed to hold the most dangerous of supernatural artifacts.

I’ve heard some commentary on the setting that implies this is a cosmic horror setting, and I’m not sure if that’s quite right. The setting is highly influenced by the Edwardian era notions of Spiritualism. In other words, there are souls and there is an afterlife, but that afterlife might go beyond the understanding of organized religion.

The setting is also influenced by fiction that was prevalent at the time that spiritualism was gaining momentum. Frankenstein introduced scientists performing dangerous experiments that could defy natural law, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which was more contemporaneous to spiritualism, introduced the idea of science being used to turn someone into a monster that they cannot control. Example supernatural effects include ghosts, cryptids, mutant animals, mysterious supernatural creatures from the other side, and psychic phenomenon.

It’s not that cosmic horror would be out of place, but it’s not the only, or even primary, form of horror in the setting. While the setting is meant to be one in which the heroes must strive against horrors, corruption, and injustice, unlike cosmic horror, the message isn’t that life is pointless when measured against the enormity of the universe, but that people that want to make a difference may have to make sacrifices to make the world a better place.

The Game System

The core system that powers Candela Obscura is derived from Forged in the Dark rules, but they have been streamlined and redirected in several places. It’s recognizable but removes some of the procedural aspects of FitD games. Blades in the Dark exists on multiple levels, the character, the crew, the holdings of the crew, and the progress of the other factions. Candela Obscura sits squarely in the active phase of characters performing investigations, with a tiny hint of the downtime phase of Blades.

Characters have ratings for different actions. These actions are organized under three broad categories, like this:

- Nerve

- Move

- Strike

- Control

- Cunning

- Sway

- Read

- Hide

- Intuition

- Survey

- Focus

- Sense

Whenever you take one of the Actions, you roll a number of d6s equal to your Action Rating. If you roll a 6 on one of the dice, you get what you wanted when you take the Action, without any complications. If you get a 4-5, you get what you want, with a complication. On a 1-3, you don’t get what you want, but something happens.

Whenever you take one of the Actions, you roll a number of d6s equal to your Action Rating. If you roll a 6 on one of the dice, you get what you wanted when you take the Action, without any complications. If you get a 4-5, you get what you want, with a complication. On a 1-3, you don’t get what you want, but something happens.

This may sound familiar, but in Candela Obscura, there isn’t any discussion about what action the player wants to use, with a response from the GM explaining how well that action works for what the character is trying to do in the narrative. There isn’t a negotiation like in Blades in the Dark, where you may ask if you can get away from an opponent by using Strike instead of Move, because you are pushing people out of the way, and the GM says, “sure, but it will have limited effect.” In Candela Obscura, If the GM thinks running away from an opponent uses Move in the scene as it has been framed, that’s what you roll.

Another deviation from the Forged in the Dark narrative are gilded dice. A number of a character’s actions may be gilded. When an action is gilded, you roll one die of a different color, and instead of taking the higher die, you can instead take the result on the gilded die. But why would you do that? Because you get back a Drive.

What are Drives? Drives are those categories under which the actions are organized. You have ratings for each of your Drives, and you can spend Drive to add additional dice to your dice pool. The actions are organized under the Drive you need to spend to boost the roll. That means, choosing to take the gilded die can be a strategic choice, potentially taking a mixed result to get back another Drive to use in a scene where you really want to boost that dice pool.

For every three points of Drive you have, you gain a Resistance in that category. When you spend a Resistance, you can reroll a number of dice equal to the rating of the action. So if you failed after pumping up your dice pool to six dice, still fail, and spend Resistance, if your Action is rated at a three, you can reroll three of those six dice.

If you’re familiar with Blades in the Dark, this reworks the use of stress and resistance rolls. Instead of softening a consequence by lowering the amount of stress taken, the character can just potentially succeed a roll they previously failed. But what happens if you fail? Well, narratively, about anything that makes sense, but in instances where a character might suffer some kind of harm, you take a number of points in your Marks. Marks come in three categories:

- Body (physical injuries)

- Brain (mental stress)

- Bleed (magical corruption)

If you take four marks in one of those categories, you instead take a Scar. If you take your fourth Scar, your character is removed from play (we’ll touch on this in a little bit). They may die, or they may just be unable to continue to operate in Candela Obscura. Each time you take a Scar, you adjust one Action down, and move another one up by one point. You then explain what the Scar looks like. If you take a Body Scar, you may have a literal Scar, while a Bleed Scar may result in you being marked by some obviously supernatural alteration.

Instead of clocks, Candela Obscura uses Countdown Dice. Any time a task isn’t something that can be resolved with a single Action, the GM rates the task with a Countdown Die, which is set to anywhere from 3 to 6. Total success counts the die down by two, a partial success moves it down by one, and a critical success, rolling a 6 on more than one die, moves the die rating down by 3. There are also Phased Countdowns, which are composed of multiple dice. When you countdown one die, something happens in the narrative that transitions to what is being addressed in the second Countdown Die. The Countdown Dice in a Phased Countdown don’t need to be set to their maximum value. It may be easy to break into an installation (a Countdown Die set to 3) but searching the building for the hidden artifact may be set to a 5.

Characters

Characters pick from one of five different roles, each of which has two specialties:

- Face (talkers that interact with other people well)

- Journalist

- Magician (the entertainer kind)

- Muscle (pick things up and hit things hard)

- Explorer

- Soldier

- Scholar (know things and research things)

- Doctor

- Professor

- Slink (sneaking and doing things unseen)

- Criminal

- Detective

- Weird (interfacing and manipulating the supernatural)

- Medium

- Occultist

From Roles, you pick from one of three abilities, and from your specializations you have six different abilities to choose from. These give you abilities that might add a die to certain dice pools under certain circumstances, they may let you automatically succeed on specific tasks by spending Drives, or being able to ask the GM questions they must answer truthfully.

Characters have three gear slots, which they don’t need to fill until they decide what to fill that slot within the course of an investigation. You might decide you need a Bleed Detector to find supernatural energies, a Bleed Container to hold an artifact safely, or a hand weapon to deal with someone that has turned into a ravenous monster beyond all reason.

The Circle has its own advancement track. Each Circle has a set number of resources that can be spent between missions to refresh character abilities. Resources allow a character to remove marks they have gained, reset drives to their starting value, or pick up a floating die that they can add to a dice pool at some point in the next investigation.

Advancement is based on questions and keys that are part of each character’s role, but this is tracked for the Circle collectively. Once the advancement track is full, the Circle gains a new ability that the players can benefit from collectively, and each character can choose from adding to their Drive or Action ratings or picking up a new ability.

There are five additional abilities that the Circle can acquire beyond Resource Management, and one of those advancements indicates that the next mission that the Circle goes on will be the last mission for the Circle. If you have a Circle with four investigators, they all answer their questions every session, and everyone hits their Illumination Keyes (roleplaying guides for each role), that means you’ll probably play through about 15 sessions before you take your One Last Run advancement, assuming you don’t want to take it earlier.

I like mechanics that nicely stand in for something more concrete in the narrative. In this case, I like the abilities that let you have a certain number of floating dice you can spend to add to an action when it makes sense to spend that resource. I’m also a fan of keeping track of advancement collectively, since the team is meant to be working together. While I know this appears in other games, the Illumination Keys remind me of Cortex Milestones, and the “lateral advancement” of shifting Action ratings to reflect momentous changes to the character reminds me specifically of the advancement ethos of Marvel Heroic Roleplaying.

Running the Game

The GM section starts by providing GM Principles. For anyone that isn’t familiar with this concept from Powered by the Apocalypse or Forged in the Dark games, these are goals the GM should be keeping in mind as they run the game. Some of these principles are about reinforcing tone and setting, while others are more about general best practices when using the system. For example, GMs are told to “show the humanity in horror, and the horror in humanity,” as well as “drive the story forward.”

When discussing Assignments, the book provides a general outline for how Assignments should be structured:

- Hook

- Arrival

- Exploration I

- Exploration II

- Escalation I

- Escalation II

- Climax

- Epilogue

The GM section notes that some Assignments may be missing some of these elements. For example, you could run a shorter Assignment by cutting out the second Exploration or Escalation scene, but the Hook, Arrival, Climax, and Epilogue are probably going to be part of most of your Assignments.

The GM section notes that some Assignments may be missing some of these elements. For example, you could run a shorter Assignment by cutting out the second Exploration or Escalation scene, but the Hook, Arrival, Climax, and Epilogue are probably going to be part of most of your Assignments.

While it’s a solid structure, if they had only explained what should appear in each type of scene, and how to frame them, it may still have been difficult to visualize if you aren’t used to building an investigative game scenario. But in addition, they provide four example Assignments, laying out the highlights of what could show up in each of these scenes. Beyond even that, each of these four examples explain what a game session might look like as players engage with the outlined Assignment. I really liked this breakdown, and as an “example of play,” it was nice to be zoomed out a little, rather than get the standard scripted scene that we often see.

In the original Blades in the Dark, there were several sections where scenarios would be discussed, and at the end of those sections, the book would ask how the reader would have adjudicated those scenarios, as well as suggesting other ways these scenarios might have gone. While not structured in the same way, I feel that these example Assignments serve much of the same purpose in this book.

There are six more Assignments included for inspiration, although these six Assignments are summarized in single paragraphs. Outside of the GM chapter, there are more examples of the kind of Assignments that might arise from the themes of each of the locations summarized for the setting. On top of those suggested events tied to different locations, the organizations, characters, and locations often have Themes listed, which in this case function somewhat like Fate aspects, in that they are meant to describe a place in terms of what its meant to convey in the story, rather than giving a highly detailed, concrete description.

The Specter in the Room

I mentioned that I was referencing the Candela Obscura material on Demiplane Nexus. Because of that online resource, I know what happens if you take your fourth scar. It is not overtly stated that when you take your fourth scar, your character is removed from play in the text of the physical print copy of the game. That said, as much as I like to avoid other reviews, I do know that there is a strain of thought that has expressed that the game is somehow incomplete or unplayable because the text did not spell out that a character is removed from play at four scars. Given that the game itself has an end state built into the progression of the Circle, in the progression rules, I think that’s a hyperbolic assertion. When you take a Scar, you are incapacitated in the scene. You narratively create a Scar and what that means. The game would still be playable if the end state was the final mission of the Circle.

Successful Assignment There is a definite appeal to a fantasy setting flavored for a specific period of history, which doesn’t have the weight of the real-world on it.

I think the streamlined version of the Forged in the Dark engine used for this game will be better equipped to bridge the gap to people that have started their roleplaying career with more traditional RPGs. I love the setting and the details it provides, as well as how those details are conveyed. Examples include the Theme summaries and Points of Interest, which do more to describe the setting in broad strokes and story beats, instead of granular, established details. I also appreciate that advancement is based on collaboratively looking at what the players achieve as a group.

Reflecting on our Losses

If you are a fan of other Forged in the Dark games, especially those that revel in the procedural details, like the original Blades in the Dark or Band of Blades, you may miss a lot of the interconnected mechanics that trigger changes and progress in the setting beyond the narrative generated in the main session. The names and artwork included in the book are very diverse, but the Fairelands are very Edwardian, and in that I mean, very turn of the (19th) century Europe, and a fantasy setting like this one could have included wider influences as part of the worldbuilding. There is a fair amount of space detailing the higher concept NPCs, like political heads of state or faction leaders, but the gameplay feels like it’s much more focused on stories that exist below that level. The high-level detail feels reminiscent of Blades in the Dark, where the PCs are growing more influential and the factions are advancing outside of PC actions, but that’s not the core gameplay loop in this game.

Qualified Recommendation–A product with lots of positive aspects, but buyers may want to understand the context of the product and what it contains before moving it ahead of other purchases.

There is a definite appeal to a fantasy setting flavored for a specific period of history, which doesn’t have the weight of the real-world on it. If you want a game where the narrative of the world is moving and generating complications in addition to the Assignments the player characters are taking on, this isn’t going to provide that. This will provide you with an engaging world that allows you to dive into investigative horror while watching your characters change with the stress and danger they encounter. Some games may give you more texture with your starting location, and others may give you more worldbuilding tools, but the game and the setting both provide enough to satisfy someone interested in looking at a new entry to the RPG horror canon.