I love a good front. Of all the tools to come out of Powered by the Apocalypse games, fronts are probably one of my favorites. (Second only to clocks, really.) Because fronts allow me to keep track of everything from the arrival of the catastrophic doomsday event to the minor rival NPC’s petty revenge plot, and they give me the tools I need to not only figure out what the bad guys are up to but also how they’re going about their nefarious deeds.

(Confession: Even though I’ve read a bunch of Powered by the Apocalypse and Forged in the Dark games, I’ve only ever run a single session of one (the original version of Dream Askew), and I’m pretty sure I ran it completely bass-ackwards. And yet my love of fronts endures.)

You know what else I love? Putting my PCs in positions of power. I love foisting eldritch artifacts or ancient magics onto their shoulders. I take glee in giving them influence within an important organization and seeing what they’ll do. It allows me to ask tough questions about how and when they use their great power responsibly (thanks, Uncle Ben). Plus, it gives my players the power to enact real change in the game – something all of us can sometimes feel powerless to do in our real lives. (My group’s go-to power fantasy is making the world a better place.)

These two loves, though – they are at odds with each other. At least, they are when it comes to my villains’ devious plotting because those fronts happen in the background. Yes, I can write down that Professor Bad Guy’s Ultimate Plan of Evil has six steps, and I can plant clues throughout the game’s narrative that could potentially lead my characters to put the pieces together and figure out his plan.

Still, I can be an anxious GM at times, worrying that my clues are too obtuse or that my players will reach the wrong conclusion. And if I fail to deliver, then they’ll fail to figure it out in time, and The Ultimate Plan will succeed without the players having had a chance to thwart it.

Now, I know some games have done a wonderful job of systematizing when fronts advance. Still, when you’re porting the concept into a game that doesn’t already have them baked into the mechanics, you’re basically running that background minigame on vibes. And on the one hand the GM can basically do whatever they want (as long as it serves the story and creates a good time for their players).

But on the other hand, the GM can basically do whatever they want, and oh gods, I was already working with themes of using power responsibly, so now I’m second-guessing my second guesses!

GIVE THEM A WAR ROOM

Fronts are meant to be a GM-facing tool — a little mini-game the GM plays with themself between sessions. When I run games, I like to flip it around and, instead, give the players a “war room.”

Maybe it’s an actual war room in the command center of their base. Maybe it’s an oracle-like NPC or familiar that keeps track of their enemies’ actions. Maybe it’s the murder board in their detectives’ office. Regardless, all of these war rooms have one thing in common – the threat map.

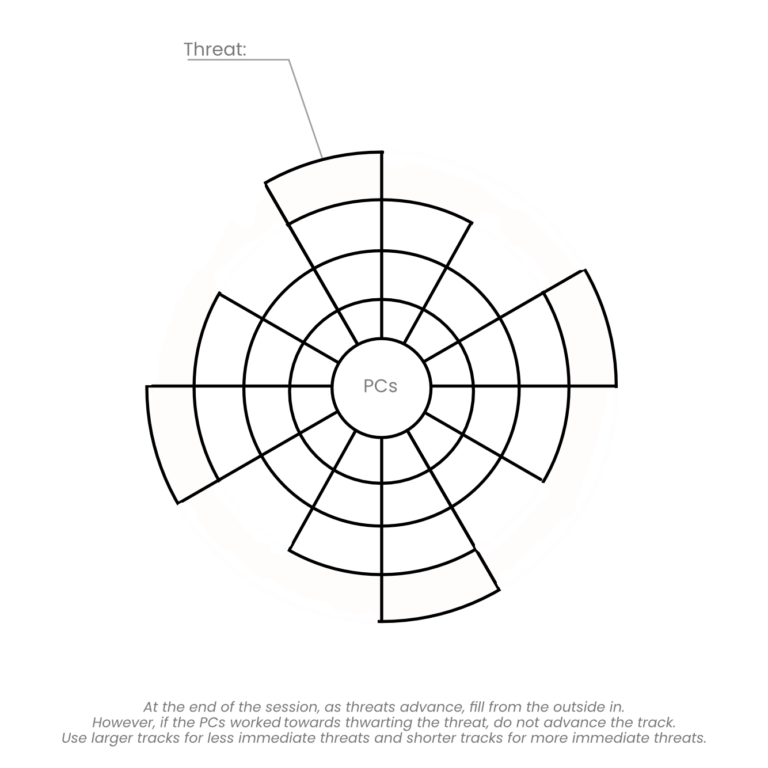

Just like fronts, the threat map is a big circle with all of the campaign’s (known) threats arranged around it like a clock. At the center of the circle are the PCs (or their town, their ship, their community, what-have-you). Each threat has it’s own number of steps, and as those steps are completed, they get filled in from the outer rim, moving towards the PCs in the center.

At the end of each session, I show my players the threat map, and together, we discuss what threats they addressed and those threats don’t advance (or get crossed off if they eliminated it).

The ones they didn’t deal with, though. Those tick down. Getting closer and closer to completion.

Of course, the threat map is fluid. As they discover more threats, they’re added to it. When they eliminate one of the threats, it’s removed.

A war room with a threat map gives your players several things – it gives the players a feeling of control (or at least the potential to feel in control), it gives them a way to prioritize the most immediate threats in the game world, and gives them a core list from which they can build out what they know about the villains’ schemes. It basically gives them a quest log.

Depending on the tone of the game and just how many enemies the players have made, I may also introduce a mitigation mechanic – some way for them to delay a threat without actually dealing with it in the session. Sometimes, it’s a die role at the end of the game. Other times, it’s a resource cost. (This is also a great place to use an NPC delegation system.)

Because while the threat map can keep your players focused on the main tasks at hand, it can sometimes make them too focused. Any mitigation mechanic you introduce will allow them to breathe and indulge in ancillary role-play that wanders a bit.

IT’S NOT FOR EVERYONE

I don’t always use a player-facing threat map when I run games. It works best in games where your players have the means to not just react to dangers but also get out ahead of them. I wouldn’t use this tool in games like Shiver or Camp Murder Lake, for example, because those games are about not being in control.

That said, introducing the threat map at a point in the game where the characters have crossed a certain power threshold could be a great way of driving home the fact that they’ve got bigger responsibilities now.

THE LAST THING I LOVE

Besides my spouse, my dog, and my library of books and games, I love one other thing — a good template.

Here’s the threat map I used when I was running Starfinder. Feel free to download it and make it your own, and tell me how you think you might incorporate player-facing threat maps into your next campaign!